Sharp-tailed Sandpiper

General Description

Similar in size and shape to the more common Pectoral Sandpiper, the rare Sharp-tailed Sandpiper can be distinguished by its rufous cap and distinctive white eye-line. Adults in breeding plumage are heavily spotted overall. Non-breeding plumage is lighter gray and less boldly streaked. Juveniles, the form most often seen in Washington, are redder than adults, with a buff-colored, lightly streaked breast, which often serves as their most distinctive field mark.

Habitat

Sharp-tailed Sandpipers breed in wet Siberian tundra. During migration, they usually stop at grassy, coastal salt marshes, although they can also be found in coastal lagoons and mudflats, especially those adjacent to salt marshes.

Behavior

In areas where they are more abundant, Sharp-tailed Sandpipers are typically seen in large flocks. In Washington, they are often seen with Pectoral Sandpipers. They feed by moving steadily along in dense grass, heads down, picking up surface prey and probing lightly. They are seen on mudflats slightly more often than are Pectorals.

Diet

On their breeding grounds, Sharp-tailed Sandpipers eat primarily mosquito larvae. Other invertebrates, including mollusks and crustaceans, are also part of the diet.

Nesting

Sharp-tailed Sandpipers are polygynous. Males with good territories mate with more than one female. Each female builds a nest out of grass on the wet, peaty tundra, or on a drier hummock. She incubates the clutch. After 19-23 days of incubation, the young hatch and leave the nest within a day or so. They find their own food immediately, but the female protects and tends them. The young birds begin to fly at 18-21 days.

Migration Status

Sharp-tailed Sandpipers are long-distance migrants. Many birds cross the Bering Strait into Alaska, where they are seen in large numbers. They then migrate down the coast, but before long veer out into the Pacific Ocean and head to wintering grounds in Australia and New Zealand. Birds seen in Washington are usually those that have not yet veered out to sea on their migration southward.

Conservation Status

The Canadian Wildlife Service estimates the worldwide population at 166,000 birds, with 1,000 birds traveling down the Pacific Coast south of Alaska each year. Because such a small percentage of the population ever makes it to the Pacific Northwest, local conservation issues involving the Sharp-tailed Sandpiper are few. Population trends are unknown. The species is listed by the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species, a global conservation effort, as 'a species that requires or would benefit significantly from international cooperative agreements under CMS.'

When and Where to Find in Washington

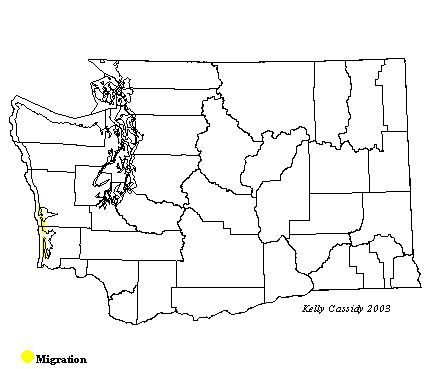

Sharp-tailed Sandpipers are rare visitors to Washington every year, and can sometimes be found in salt marshes and mudflats on the coast, from mid-August to mid-November. They are most likely seen in October. Eastern Washington wetlands are also rare, fall stopover points for migrating Sharp-taileds, from early September into mid-October. The salt marshes at Ocean Shores (Grays Harbor County) are the best spots for locating them.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | R | R | R | |||||||||

| Puget Trough | R | R | ||||||||||

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | ||||||||||||

| Okanogan | ||||||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau |

Washington Range Map

Family Members

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria

Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes

Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes Wandering TattlerTringa incana

Wandering TattlerTringa incana Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca

Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca WilletTringa semipalmata

WilletTringa semipalmata Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes

Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda

Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda Little CurlewNumenius minutus

Little CurlewNumenius minutus WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus

WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis

Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus

Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica

Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica

Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa

Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres

Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala

Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala SurfbirdAphriza virgata

SurfbirdAphriza virgata Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris

Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris Red KnotCalidris canutus

Red KnotCalidris canutus SanderlingCalidris alba

SanderlingCalidris alba Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla

Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla Western SandpiperCalidris mauri

Western SandpiperCalidris mauri Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis

Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis Little StintCalidris minuta

Little StintCalidris minuta Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii

Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla

Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis

White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii

Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos

Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata

Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis

Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis DunlinCalidris alpina

DunlinCalidris alpina Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea

Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus

Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis

Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis RuffPhilomachus pugnax

RuffPhilomachus pugnax Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus

Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus

Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus

Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata

Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor

Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus

Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius

Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius